News Analysis

By David Bolling

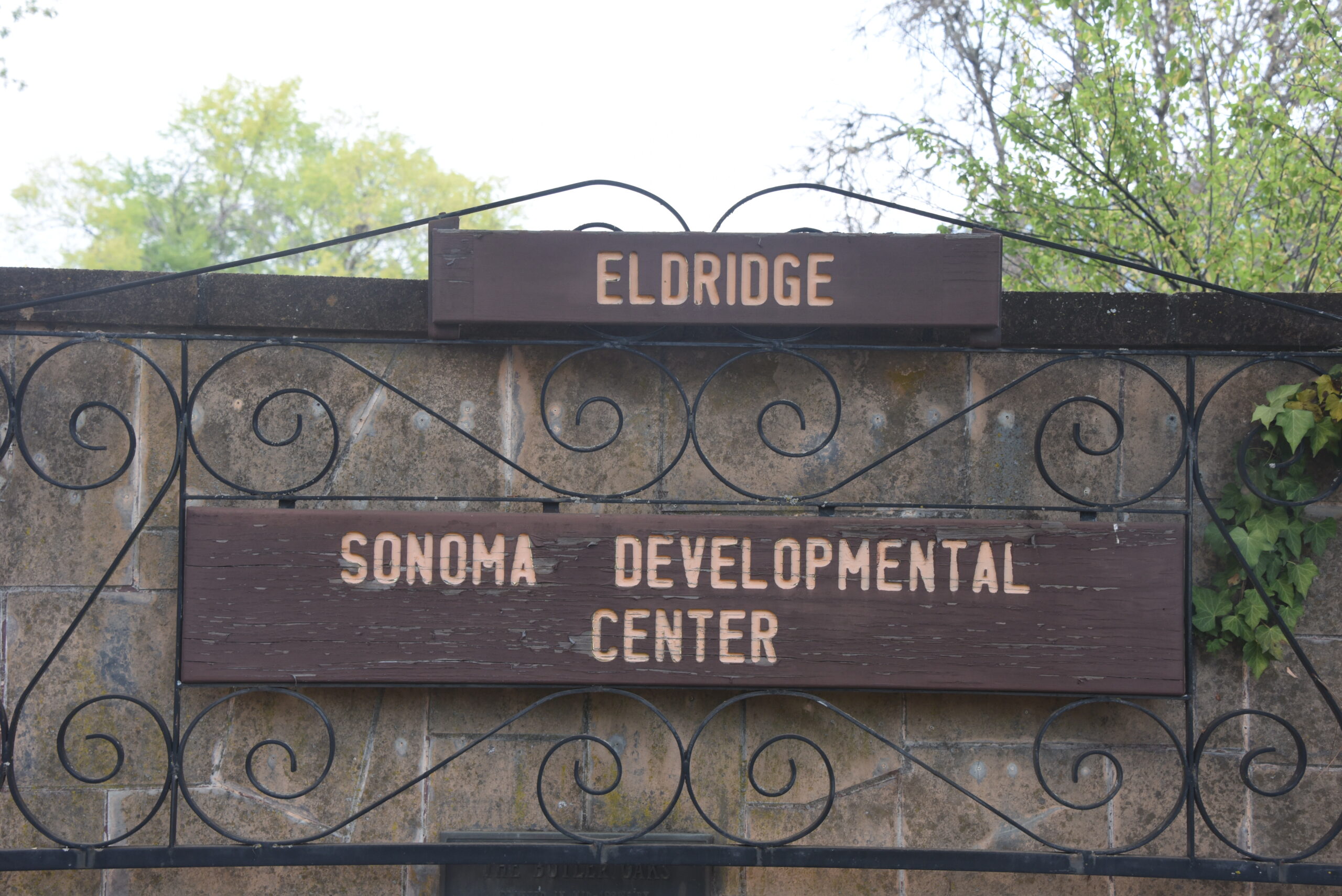

There is a pall hanging over the Sonoma Developmental Center, where record levels of triple-digit heat have singed the lawns and playing fields, pushed oaks and redwoods past their vascular limits, evaporated weeks of water from the surface of both Fern and Suttonfield Lakes and ratcheted up the risk of another catastrophic wildfire like the last one in 2017.

But that’s just the meteorological misery afflicting the 945-acre property. A land-use decision with profound consequences for all of Sonoma Valley is looming on the long-awaited SDC Specific Plan that will determine the fate of the iconic Sonoma Valley site.

Since the center was closed, and it’s last developmentally disabled occupants were distributed (or “transitioned” in the argot of the California Department of Developmental Disability) to small group homes scattered around the Bay Area in 2018, the State has been aggressively pushing a timeline to shed itself of the financial burden of owning the property.

All the open space outside the 185-acre central campus has already been promised to the state and county parks departments, but the state government will not allow those lands to be transferred until a final plan for the central campus has been adopted.

In collaboration with the County of Sonoma, the State Department of General Services (DGS) has decreed that a Specific Plan for the property, and its attendant Environmental Impact Report, must be completed and approved by the end of this year. As if to provide a little extra incentive to push that process forward, in May DGS released a public Request For Proposals to encourage developers to submit bids on the property, with a deadline of July 15. So far DGS has released no information regarding who – if anyone – has responded to the request, and there is some question about why any serious developer would submit a bid on a property for which the County has not yet completed a Specific Plan with zoning and General Plan amendments.

A 198-page draft version of that plan, along with a 789-page Draft Environmental Impact Report, was released for public review August 10, and the public reception in Sonoma Valley was not happy.

The proposed plan – a variation on one of three options previously released by the county – calls for 1,000 housing units, and a resident population of some 2,400 people, with a work force for 940 on-site jobs. Included in the 1,000 homes would be at least 283 “affordable” units with deed-restricted rent or ownership levels tied to resident’s incomes. Additional housing, mandated by the legislation enacted to authorize and guide SDC’s transformation, would include “at least” five parcels designated for homes to house people with developmental disabilities.

Also included in the plan is a 120-room luxury hotel, live-work artist studios, an institute and/or retreat center, research and development spaces, some retail stores, possibly a small institutional campus, a community gym and a revitalized farming operation referred to as the “Agrihood.”

County staff have gone to great lengths to define and describe an appealing mix of residential, commercial, agricultural, recreational, retail, research and development uses and facilities for the site. But the proposed scale of on-site housing – with 2,400 new residents – continues to trouble Valley locals, particularly those living in Glen Ellen, which had a 2020 census population of just 734 people.

And part of the problem with the Specific Plan is that it’s not very specific. Some critics view the proposal to build new housing for developmentally disabled residents as supremely ironic, given the state’s determined efforts to remove them all from the facility five years ago. More to the point, the Specific Plan contains no specific housing numbers, no cost estimates, no description of the services that would need to be provided 24/7 for developmentally disabled care, were the funding would come from, and no specific site location on the property.

There is also appealing language in the Plan to preserve the heritage and legacy of indigenous people at SDC, but no specifics about how, where and at what cost.

The Specific Plan presents a vision of a “hospitality hub” built in and around the historic Main building at the top of the SDC horseshoe, but that building, while it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, has been closed for decades and the cost of restoration and mitigation has been estimated at tens of millions of dollars.

The water resources of SDC, prominently including the impoundments at Fern Lake and Suttonfield Lake, are noted as major environmental resources, but there is no discussion in the EIR text about the seismic safety of the dams creating those lakes, which were constructed long before the full extent of risk was known on the Rogers Creek-Hayward fault system, which extends along the west side of Sonoma Mountain just west of SDC. USGS scientists say the two sides of the fault are slipping past each other at the rate of six-to-ten millimeters per year, and they estimate there is a 33-percent-to-62 percent chance of a 6.7 magnitude earthquake during the 30-year period between 2014 and 2043.

But the Plan’s EIR utterly ignores that expert opinion. Instead, the EIR states, “Implementation of the Proposed Plan would not expose residents, visitors and employees, as well as public and private structures, to substantial adverse effects, including the risk of loss, injury, or death involving rupture of a known earthquake fault; strong seismic ground shaking; seismically related ground failure, including liquefaction; or landslides.”

While seismic safety issues are essentially ignored in the Specific Plan EIR, the issues related to wildfire risk are addressed directly through proposals for fire-safe building code standards and creation of defensible space around structures. But there are only two evacuation routes out of the Valley – Highway 12 and Arnold Drive – and the danger of those routes being clogged by 2,400 more Sonoma Valley residents during a wildfire event is virtually dismissed. That despite the fact that both the Highway 12 and Arnold Drive-Warm Springs Road routes were clogged during the 2017 wildfire evacuations, and that the 2020 Glass Fire completely closed Highway 12 near Oakmont.

Still, says the EIR, “Implementation of the Proposed Plan would not impair implementation of or physically interfere with an adopted emergency response plan or emergency evacuation plan … (and) Implementation of the Proposed Plan would not expose people or structures, either directly or indirectly, to a significant risk of loss, injury or death involving wildland fires.”

That conclusion ignores the fact that the streambed of Sonoma Creek, which transects the east side of SDC and is choked with woody debris, channeled the 2017 Nuns Fire into the adjacent Eldridge subdivision, where it destroyed one house, a garage, and sent burning embers into nearby yards that could have spread to scores of houses if the chance arrival of a Valley of the Moon fire truck had not intervened.

In all the 789 pages of the SDC Specific Plan EIR, there is not a single environmental issue on the entire 945-acre site that the document states would require any mitigation measures. And yet there is no assurance in the Specific Plan that the lofty commitment to sustainable policies and goals detailed in the plan would actually be implemented.

In the words of Tamara Galantar, a consulting attorney to the Sonoma Land Trust who specializes in analysis and application of environmental impact reports, the EIR appears to be stating that the Specific Plan will be “self-mitigating.”

The EIR appears to duck the mitigation dilemma altogether by stating, “As a programmatic document, this EIR does not assess project-specific impacts that may result from developments pursuant to the Proposed Plan. To the extent that any future development project made possible by the Proposed Plan may have individual, site-specific impacts not addressed in this program EIR, such projects would be subject to separate, project-level environmental review, as required by State law.”

Other baffling EIR assertions include the conclusion that the plan “would not induce substantial population growth in an area, either directly (for example, by proposing new homes and businesses) or indirectly (for example, through extension of roads or other infrastructure).”

And the Specific Plan EIR acknowledges that increased traffic congestion along Arnold Drive would be “significant,” and that mitigation strategies to reduce Vehicle Miles Traveled “may be insufficient” to reduce traffic “below the applicable significance threshold.” Mitigating traffic impacts, the EIR blithely concludes, may not be possible, “because there are no other feasible mitigation measures available.”

In sum, as far as the current draft of the Specific Plan EIR is concerned, accommodating 2,400 new residents in Glen Ellen – a village with a little more than a quarter of that population – will have no negative impacts on threatened and endangered species, on a critical wildlife corridor connecting Sonoma Mountain to the Mayacamas range, will not put new or old residents at greater risk from wildfires and a major seismic event, and may increase traffic congestion significantly, but that impact is “unavoidable.”.

To read the SDC Specific Plan and the EIR that accompanies it, go online to sdcspecificplan.com.